Thomas William Ruston

My doctoral work focussed on the reception of John Zizioulas’ eucharistic ecclesiology and trinitarian theology in the West by Social Trinitarianism; in which I made the argument that Zizioulas does not argue for a social trinity. But in this talk, I wish to identify Zizioulas’ unique contribution to Orthodox theology. I intend to argue that it lies with Zizioulas emphasising the eschatological dimensions of the Eucharist. Therefore, I wish to bring John Zizioulas’ ecclesiology into critical dialogue with the relationship between Christ, the liturgy and the Church in the ecclesiologies of Vladimir Lossky and Georges Florovsky.

My doctoral supervisor advised me that to understand a concept we must discern the question or problem which a theologian posed their concept as the answer. I spent much of my thesis discerning that the question which motivated Zizioulas was that, and I quote, ‘as long as we fail to tackle the question, “what is the Church?”, we shall never reach agreement in the ecumenical movement’[1]. For Zizioulas the ecumenical endeavour consists of the quest to return to the authentic catholicity of the Church and which must include both the West and the East as the one body of Christ. Vladimir Lossky, Georges Florovsky and Zizioulas are united in their response that the Church must not be considered first as an institution or simply a community of believers, but as the whole Christ, the Spiritual and mystical body of Christ.

Zizioulas conceives of the Church as participating in the filial relationship that the divine Son has eternally with the Father. The Church Fathers called this participation, theôsis. The Church exists precisely to enable this adoption into that filial relationship: Zizioulas writes that,

The “Mystery hidden before all ages” is that the will of the Father is nothing else but the incorporation of this other element, us, or the many, into the eternal filial relationship between the Father and the Son. The mystery amounts, therefore, to nothing but the Church[2].

Thus, for Zizioulas as it is for Georges Florovsky, and to some extent Vladimir Lossky, the discussion on eucharistic anamnesis is a logical working out of the proclamation that the Church exists as the spiritual body of Christ. As Florovsky himself wrote: ‘one can evolve the whole body of Orthodox belief out of the Dogma of Chalcedon’[3]. And Zizioulas claims that ‘the theology of the Church is but a chapter and a vital chapter of Christology. Without this chapter, Christology itself would be incomplete’.

For Zizioulas, the answer to the question ‘what is the Church’ emerged through his discussion on anamnesis in Florovsky’s ecclesiology, and the two economies of the Son and of the Spirit in Vladimir Lossky- so Zizioulas frames the discussion on the relationship between history and eschatology in the eucharistic anamnesis in terms of the Church as the corporate personality of Christ. Thus, for Zizioulas as it is for Georges Florovsky, and to some extent Vladimir Lossky, the discussion on eucharistic anamnesis is a logical working out of the proclamation that the Church exists as the spiritual body of Christ.

However, the conception of the Church as the ‘totus Christus’, the whole Christ, argued by Vladimir Lossky and Georges Florovsky, raises the important and unresolved issue of the relationship between Christology and Pneumatology in relation to the Church. Whilst the Church may be fully identified with the hypostasis of Christ, the question still remains as to how Pneumatology and Christology can be brought together into a full and organic synthesis. And Zizioulas writes that ‘it is probably one of the most important questions facing Orthodox theology in our time[4].’

Zizioulas writes that the task of relating ‘the institutional with charismatic, the Christological with the Pneumatological aspects of ecclesiology, still awaits its treatment by Orthodox theology’[5]. For Zizioulas, neither Georges Florovsky nor Vladimir Lossky gave a satisfactory response, and he writes that

‘Florovsky indirectly raised the problem of the synthesis between Christology and pneumatology, without however offering any solution to it. In fact there are reasons to believe that far from suggesting a synthesis, he leaned towards a Christological approach in his ecclesiology’[6].

Zizioulas still requires an account of a pneumatological understanding of the Church as the outworking of a Chalcedonian logic of Christology. In relation to Zizioulas’ solution to this problem I wish to discuss the two major problems Zizioulas identifies as implicit to the ecclesiologies of Georges Florovsky and Vladimir Lossky.

First, Zizioulas challenges a view of eucharistic remembrance as merely the commemoration of a past event which abides in the present. This was argued by Georges Florvosky.. Florovsky claims that ‘the eucharistic anamnesis is a remembering of Christ’s salvific act at a singular point in history, i.e. the Last Supper, which the Spirit manifests in the present because the Spirit abides in the Church. Florovsky writes that ‘the Holy Ghost does not descend upon earth again and again, but abides in the ‘visible’ and historical Church’[7].

The problem implicit to Florovsky is an emphasis on Christology that does not give equal prominence to the Spirit because the Spirit is treated as an attendant to the mystery of the incarnation. Moreover, Florovsky’s account can fall into the danger of confining the Church exclusively to a historical process, Christ has achieved salvation which then abides in the present until the eschaton.

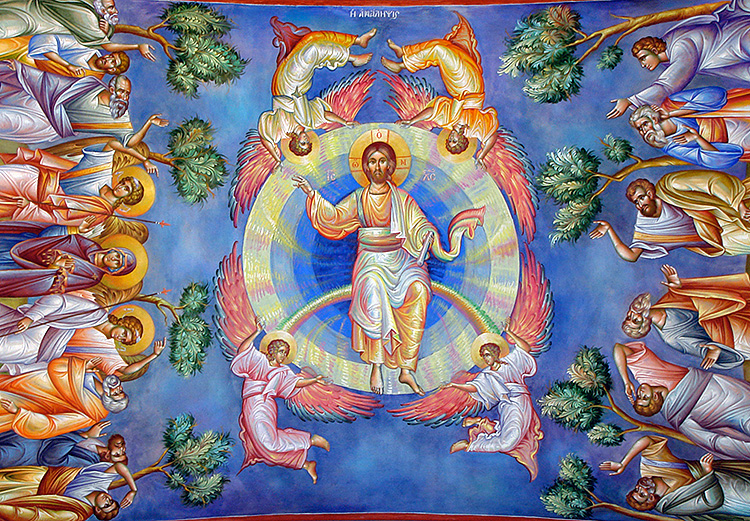

Instead, Zizioulas sees the Eucharist as both a revelation of the Church itself and as an icon of the Kingdom in which the eschaton is made manifest.

Zizioulas’ solution is to unify the Eucharistic anamnesis with the epiclesis of the Spirit, as he writes ‘‘Eucharistic remembrance is inconceivable apart from the Eucharistic epiclesis’[8]. Zizioulas turns to Maximus the Confessor to maintain that the Eucharistic anamnesis is the memory of the future, such that the whole of God’s historical purpose, up to its consummation in the Second Coming, is made present in the Eucharist. This makes Christ manifest in the Church not from solely from the past, but collapses the division of past, present, and future by manifesting the eschaton in the Church’s Eucharistic liturgy, arguing that

‘The Eucharist as a remembrance in the context of epiclesis leads a conception of history which eliminates any question of ‘renewing the Supper and the sacrifice of Christ- accomplished once for all’[9].

Instead, Zizioulas advocates another view of history. Salvation is always within the realm of pneumatological action. Zizioulas advocates the eucharistic anamnesis as not merely the remembrance of the Last Supper, or even the last supper made present, but that the Last Supper itself ss an eschatological meal.

When the eucharistic elements are identified with the lamb, as is the case in the Last Supper, the ‘blessing’ itself and the ‘memorial’ itself no longer relate to God’s past action in history, but now relate to an imminent reality- i.e. the sacrifice that will take place the next day and also all that will follow after, including the future Kingdom where Christ will eat this meal ‘new’ with his disciples. Therefore, the ‘memorial’ of the Last Supper has several eschatology dimensions: through it, in the present, the past becomes a new reality, but the future becomes a reality that is already.’ (Zizioulas, Biblical Aspects of the Eucharist, p.6).

This leads to the second problem with a historical view of eucharistic anamnesis. Both Georges Florovsky and Vladimir Lossky have a tendency to purport two distinct economies of Christ and of the Spirit. This is problematic because it conveys the divine economy in terms of a schematic procession, namely divine economy is an achievement established by Christ which the Spirit then completes.

Zizioulas discusses the issue of pneumatology and Christology in relation to divine economy and thus identifies the Church with one divine economy accomplished in the person of Christ as a pneumatological entity, a “corporate personality”. In contrast to his own view of the Church as totus Christus, he found Lossky’s solution deeply problematic because it schematizes the economic role of the Son and the Spirit respectively.

Lossky treated the synthesis between pneumatology and Christology by means of the distinction, so characteristic of his theology, between nature and person. He said:

‘The work of Christ concerns human nature which He recapitulates in His Hypostasis. The work of the Holy Spirit, on the other hand, concerns persons, being applied to each one singly … The one [Christ] lends His hypostasis to the nature, the other gives his divinity to the persons’ (Lossky, Mystical, p.166-167)

In a slightly different emphasis to Florovsky, Vladimir Lossky did not regard Pentecost as the continuation of the incarnation but ‘it is its sequel, its result. That is, the economy of the Son is to deify human nature in general. Whilst the economy of the Spirit is to complete the work of Christ by deifying individuals. As Lossky claims, ‘the work of Christ unifies; the work of the Spirit diversifies’ (Lossky, mystical, p.167). Leading to Lossky’s well known phrase that the Church is the image of God because ‘the multitude of saints will be his image’[10].

Whilst Zizioulas agrees with the distinctiveness of hypostasis of the Spirit, in terms of the divine economy Zizioulas writes that ‘the divine economy is only one and that is the Christ event’[11].

We cannot speak of two sequential economies. For this reason, in Zizioulas’ view Christology can never be separated from pneumatology, Christology is always conditioned by the Spirit, and he argues that

‘because of the involvement of the Holy Spirit in the economy, Christ is not just an individual, not “one” but “many”. This “corporate personality” of Christ is impossible to conceive without pneumatology. It is not insignificant that the Spirit has always, since the time of Paul, been associated with the notion of communion. Pneumatology contributes to Christology this dimension of communion. And it is because of this function of pneumatology that it is possible to speak of Christ as having a “body” i.e. to speak of ecclesiology, of the Church as the body of Christ.’[12]

By conceiving of the Church as the corporate personality of Christ, in which the one and many are unified, Zizioulas argues that the ‘pneumatological dimension of the Church lies precisely in that it transcends linear historicism by making the eschaton part of the anamnesis of the Church.’>[13]. This is because Zizioulas readdresses the problem of a processual view of two economies by postulating the one divine economy of Christ which is the revelation of our eschaton as participation in the hypostasis of Christ.

Zizioulas’ Solution

The Eucharist therefore is both a remembrance of the eschaton, and at the same time the descent of the eschaton into history. He writes,

when the eschata visits us, the Church’s anamnesis acquires the eucharistic paradox which no historical consciousness can ever comprehend, i.e. the memory of the future, as we find it in the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom…[14].

The Spirit does not enter into history and abides there, for that is the unique vocation of the Son, rather Zizioulas uses the language of epiclesis, in which the Spirit breaks into the present from the future. Eschatological reality does not drive historical life continually from within but rather draws it from without. The Spirit cuts across history, manifesting the eschatological mystery of the new creation in Christ, he writes:

‘The eschatological penetration is not a historical development which can be understood logically and by experience; it is a vertical descent of the Holy Spirit, by the epiclesis– the epiclesis which is so fundamental and so characteristic in Orthodox liturgy- which transfigures the “present age” and transforms it in Christ into the “new creation”[15]

The Church exists as the whole Christ, not as achieved in one historical time, but that the ontological fullness of the Church is manifested in Christ and the Spirit. For Zizioulas that this does not mean that history and the past work of Christ are not given their true value, but that their value is always conditioned by the coming of the Spirit.

In conclusion, although we could criticise Zizioulas for advocating an over realised eschatology in the eucharistic liturgy. Zizioulas reminds us as predominantly Western Christians of the importance of viewing the Eucharistic remembering within the two categories of communion and eschatology.

Zizioulas draws from both Lossky and Florovsky the importance of catholic consciousness in the Church which consists of the notion of the Church as the unique subject of multiple persons becoming one in the persons of Christ and the Spirit, where persons are constituted through their participation in the trinitarian life, a life characterised as the mutuality of self-giving. But by entering into critical dialogue with Lossky and Florovsky Zizioulas reminds us that eschatology is not a matter of the last stage of a linear view of history. Rather Eschatology is the realisation of divine-human communion precisely because the divine Son became history in his incarnation; and this is realised in the Eucharist as that moment of the many becoming one in Christ by the Spirit drawn into communion with the Father. The importance of the Spirit is that it confronts the process of history with its consummation, with its transformation and transfiguration.

Thus, Zizioulas may agree with Lossky that the Church exists as the image of God as ‘the multitude of saints will be his image’ but only because, for Zizioulas, that multitude of saints subsists as the “corporate personality of Christ” who always exists as both “one” and the “many” through the synthesis of the Spirit and Christ. Thank you for listening to my talk.

[1] Zizioulas, 2010, The Mystery of the Church in Orthodox Tradition, p.146.

[2] Zizioulas, ‘The Mystery of the Church in Orthodox Tradition’, p. 143.

[3] (Florovsky, Patristic theology and the ethos of the Orthodox Church).

[4] John Zizioulas, Being as Communion (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1985), p. 126.

[5] Zizioulas, Being as Communion, p. 125.

[6] Zizioulas, Being as Communion, p. 124.

[7] Florovsky, ‘The Catholicity of the Church’, p.45.

[8] Zizioulas, ‘Biblical Aspects of the Eucharist’, p. 8.

[9] Zizioulas, ‘Biblical Aspects of the Eucharist’, p. 9.

[10] Vladimir Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 1957), p. 173.

[11] Zizioulas, Being as Communion, p. 130.

[12] Zizioulas, Being as Communion, p. 131.

[13] John Zizioulas, ‘The Pneumatological Dimension of the Church’, in The One and the Many: Studies on God, Man, the Church, and the World Today (Alhambra, California: Sebastian Press, 2010), pp. 75–91 (p. 79).

[14] Zizioulas, Being as Communion, p. 180.

[15] John Zizioulas, ‘The Eucharistic Vision of the World’, in The Eucharistic Communion and the World (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2011), pp. 123–31 (p. 130).

Source: Thomas William Ruston