Speech delivered at the 1988 Lambeth Conference of Anglican Bishops

Metropolitan John (Zizioulas) of Pergamon

I. It is a great honor for me to be invited to address this august assembly, the historic Lambeth Conference of Anglican bishops, which for more than a hundred years now has been an event of great significance not only for the Anglican Church but also for the worldwide Christian This invitation constitutes for me a sign of true ecumenical spirit on the part of the Anglican Communion, a most encouraging and hopeful sign for the future of the Church’s unity. It indicates clearly that no Christian church can or does any longer act or speak, or even think and debate—I dare also say decide—in isolation. I trust that such an interpretation, on my part, of this gesture of the Anglican Church—an interpretation, that is, which sees in this gesture far greater and essential significance than a mere act of courtesy—does not sound too presumptuous. Although I should not for a moment forget that I am here as an invited guest to attend as an observer and speaker the proceedings of a body that does not formally belong to my own Church—and I should, therefore, bear in mind all the time that whatever I say should be expressed with the utmost care not to appear as interfering with the affairs of another church—I nevertheless boldly assume that whatever is being said or even decided in this conference is a matter of concern for me and for my Church, too. After all, our two churches are engaged in official theological dialogue and can no longer say to one another on essential matters of faith and order, “this is our business; you keep out of it.” Such an attitude would strongly contradict and even damage the ecumenical spirit lying behind the invitation that has brought me before you today. I should, therefore, like to express my deep gratitude to the Archbishop of Canterbury for this invitation, mainly because it portrays a consciousness of “interdependence”—a term so central to his address of last night. And I shall try in all humility to submit for your consideration certain thoughts provoked in me by his rich and important address. I beg you to receive these thoughts as coming from a fellow Christian and bishop who has been deeply engaged in ecumenical dialogue for a long time and whose Church treats the Church’s unity and its restoration as a matter of greatest importance, indeed as a subject of daily eucharistic prayer.

II. What can an Orthodox say to an assembly of Anglican bishops? How can the Orthodox tradition be of any relevance to a church formed historically and spiritually by what is called “Western Christianity,” both Roman and Protestant? We have been accustomed to divide Christendom in two parts—or more recently three: the East, the West, and now also the so-called “Third World.” While this tripartite division is due mainly to social and political reasons, that of the East-West scheme is not only cultural but to a great extent also It points to a difference in mentality and approach in theology and church life, perhaps also to a different ethos. The Christians of the East have always been preoccupied with different problems from those dominating the Christians of the West. The late Cardinal J. Daniélou, in his work entitled The Origins of Latin Christianity, singles out certain features that make up the typical characteristics of Western Christian thought as early as the time of Tertullian. They include: a strong interest in history, a preoccupation with ethics, and a deep respect for the institution, sometimes to the point of being legalistic about it. St. Augustine, later on, owing to the crisis facing Western civilization in his time, introduced a dimension that was bound to create a dichotomy within Western Christianity from that point onward, namely the importance of introspectiveness, consciousness, and the inner man, from which sprang the important mystical, Romantic, and pietistic movements of the Christian West. The East, on the other hand, seems to have always been preoccupied with an eschatological, metahistorical outlook that tends to relativize history and its problems. This has sometimes led to an undermining of the historical and political issues or even of missionary activity. But it has also had some positive consequences. The institution has always been central to the Orthodox tradition but has never been conceived purely or primarily in historical and legal terms. Authority in the Church was always placed in the context of worship, particularly the Eucharist, and was thus conditioned by the eschatological outlook in two main respects: through Pneumatology, which makes of the institution an event, and through communion, which makes the authority of the institution constantly dependent on the community to which it belongs. This preoccupation with eschatology has made it inevitable to look always for the absolute, the ultimate theological raison d’être of the institution and never to regard it as a matter of juridical potestas transmitted through a code of law.

This has had several concrete consequences in Church life and theology. It has helped the Church, for example, to avoid problems such as clericalism or the clash between charisma and institution. It has made it unnecessary to develop Pentecostalist movements, and, perhaps one may be bold enough to suggest, it has accounted for the fact that a problem so central in the present debate within Anglicanism—and the broader Western Church—as that of the ordination of women has not been an issue in the Orthodox Church.

All this may imply that there is little or nothing in common between the Orthodox and the Western Churches, and that the Orthodox should not bother to deal with the problems facing the Western Churches, nor should the Western Christians pay any attention to what “exotic” Orthodoxy says concerning these problems. In fact, there are many, alas too many, on both sides that think in this way. There are many Orthodox, for example, who watch what is happening in Anglicanism with the coolness and the arrogance of the outsider—a sort of “who has appointed me my brother’s keeper” attitude—and there are many, alas too many, Western Christians who do not give a penny for what the Orthodox think when it comes to their own institutional matters and who at best allow Orthodoxy to have a say in matters of spirituality and worship.

We thus witness an ecumenical movement still dominated by the past and unable to see that we all—Easterners and Westerners as well as Third World people—live in an increasingly unified world, in a world of interdependence, to use again this important point of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s address, in which no geographic part of the Church can be self-sufficient and no tradition can say to the rest, “I need thee not.” We have to think, act, and decide on the basis not of what we want, but what the world demands and really needs in order to have a future, that future promised by God eschatologically in Christ.

With such thoughts in mind, I wish to offer some modest comments on what the Archbishop of Canterbury has so pertinently pointed out in his address. And first, I should like to comment on what the Archbishop has called “internal” matters of unity of the Anglican Communion. Of these matters, I should like to mention two in particular. They are both interrelated. And they are both far from irrelevant for the Orthodox themselves.

The question of central authority

The Orthodox are known for their decentralized way of church organization. The system of “autocephaly” involves an organization whereby no central authority has the power to dictate to the rest what to do, leaving the final decision to a common agreement between the local Churches, and debating the issues for as long as it is necessary in order to reach unanimity or at least common consensus. I was struck by the Archbishop’s reference to a similar attitude he had once observed among the African Christians. It is an interesting indication of how much we need each other and how useful everyone’s experience is in the ecumenical movement.

Now, this system of autocephaly and synodical practice is undergoing a certain shift of emphasis in our time. This does not involve any radical departure from Tradition, but rather an application of its most fundamental principles. The “many” always need the “one” in order to express themselves. This mystery of the “one” and the “many” is deeply rooted in the theology of the Church, in its Christological (the “one” aspect) and pneumatological (the aspect of the “many”) nature. Institutionally speaking, this involves a ministry of primacy inherent in all forms of conciliarity. An ecclesiology of communion, an ecclesiology that gives to the many the right to be themselves, risks being Pneumatomonistic if it is not conditioned by the ministry of the “one,” just as the ecclesiology of a pyramidal, hierarchical structure involves a Christomonistic tendency, which undermines the decisive role of the Holy Spirit in the life and structure of the Church. We need to find the golden mean, the right balance between the “one” and the “many,” and this I am afraid cannot be done without deepening our insights into Trinitarian theology. The God in whom we believe is “one” by being “many (three),” and is “many (three)” by being “one.”

The question of central authority in the Church is a question of faith and not just of order. A Church that is not able to speak with one mouth is not a true image of the Body of Christ. The Orthodox system of autocephaly needs and in fact has a form of primacy in order to function, and I dare think that the same would be true of Anglicanism. The theology that justifies or even (as an Orthodox, and perhaps an Anglican, too, would add) necessitates the ministry of episcopacy, on the level of the local Church, also underlies the need for a primacy on the regional or even the universal level. It would be a pity if Anglicanism were to move in the opposite direction; it would then have to look for a noninstitutional kind of identity, and the result would be ecumenically unfortunate, perhaps tragic. The Orthodox need the unity of the Anglican Church, because they have a vision of unity based not on confessionalism (which seeks to profit from the divisions of others), but on the concept of Una Sancta as a reflection and an image of the eschatological unity of all in one body. The unity we seek is neither one of absorption in a confessionalistic sense, in which one church absorbs another, nor one of a “reconciled diversity” in which the Church is made up of confessional bodies that bear no structural relation whatsoever to each other. We must work toward a unity in which, in the inspired words of Archbishop Runcie, confessional identities must be ready like tents to dissolve themselves in order to become the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. But, for this, it is important not to lose sight of the experience of institutional unity in the present provisional state of confessional existence, for without such an experience no progress toward an organic, visible unity of the Church can be made. Anglicanism has, in spite of its contact with the Reformation, preserved episcopacy as an institution of visible unity. After the surprising experience of BEM, we can regard this as a positive factor for the conception of the unity we seek, for it emerges now that episcopacy, properly understood or even, if necessary, reformed, can be the basis of a widely acceptable visible unity. It is in this direction that conciliarity, too, including the function of primacy, can be made into a matter of visible unity. We live at a critical moment in the history of the ecumenical movement, and the direction in which Anglicanism chooses to move with regard to its institutional unity will affect decisively the nature of “the unity we seek” for all of us. Far from being an “internal affair” of Anglicanism, its unity is a matter of vital concern for the whole Church.

This leads me now to take the liberty of saying a few words concerning the following debated issue.

The ordination of women to the priesthood

On this point, I should like to begin by speaking bluntly and openly to you. It is no secret that the Orthodox are officially opposed to any decision of the Anglicans to ordain women to the priesthood, let alone the episcopate. Looking at the matter with a confessionalistic spirit, any split in Anglicanism on this matter can “benefit” the Orthodox (and also the Roman Catholics). But in a nonconfessionalistic approach to the ecumenical movement, any such split would be extremely undesirable. I personally believe that Orthodoxy is not confessionalistic in its spirit—quite the contrary—and would, therefore, be anxious to see that the unity of the Anglican Church is maintained at all costs. Of course, it is not for me, an Orthodox, to say to the Anglican Church how to do this. I can only make a plea and voice my concern on a matter affecting the unity of the entire Church, such as this one. I can, nevertheless, underline what Archbishop Runcie pointed out in his address when he referred to cases of conflict in the early Church, both New Testament and patristic. When conflicts of such acuteness arise, this history of the early Church teaches us that no decision should be reached without an exhaustive theological debate of the issue. The letters of St. Paul in their majority illustrate this with regard to the issue of the way the Gentile Christians were to be admitted into the Church. And the fourth-century patristic literature speaks clearly of the length of the theological discussion that preceded all final decisions concerning the thorny issues related to Arianism. It took two generations, that of Athanasius and that of the Cappadocians, to clarify the issues theologically. Without an exhaustive theological debate, no conflict can be creatively overcome or resolved in the Church.

It seems to me that we have not even begun to treat the issue of the ordination of women as a theological problem at an ecumenical level. Those opposing it have so far produced only reasons amounting to traditional practice, while those supporting it often appear to their opponents to be motivated mainly by sociological concerns.

Before the matter comes to voting, it may be wise and more appropriate to the nature of the issue to debate it on an ecumenical level theologically: what is it in the nature of priesthood that prevents women from being ordained to the priesthood? And what is it, apart from perhaps serious and important social reasons, that necessitates the acceptance of women into the priesthood? Theology being a reflective discipline may often appear to be an obstacle to quick action. But is this necessarily wrong? Are we to turn theology into a secondary or even irrelevant matter in the unity we seek? Looking at the way ecumenical affairs are conducted in our time, one is forced, sadly, to think that this is already the case in the ecumenical movement of our days. But the cost of this can be too great for the Church of Christ to pay. As an Orthodox theologian, I feel rather strongly about this, and I cannot but express this feeling to you on this occasion.III. But the Archbishop’s address was so rich and so broad in the areas it covered that the two points I have just discussed form only a small part of what this address has meant to me as an Orthodox It would not do justice either to the address or to my sensitivities as an Orthodox if I did not say how important I regard the broader perspective in which the Archbishop put the entire question of Church unity. I have in mind in particular two points made so forcefully by the Archbishop. One is the point that we cannot seek the unity of the Church apart from the broader issue of the unity of humankind, and indeed of the whole created world. Looking at this from the standpoint of the Eucharist—a standpoint that both Anglicans and Orthodox share—one cannot but underline this point very strongly. The Church exists in order to proclaim salvation from all forms of brokenness and division, whether of a social or a natural kind. The catholicity of the Church begins from the Eucharist where natural and social divisions such as age, sex, race, class, profession, etc., are overcome in the Body of Christ. The Church does not possess the power to bring about the overcoming of these divisions in history; indeed she believes that no human power whatsoever has such an ability. But this does not excuse her for being indifferent to these divisions wherever and whenever they may appear. By word and sacrament, by preaching and not least by her institutions and structures, the Church must proclaim the transcendence of such divisions and be, in this way, a sign of the Kingdom. It is, therefore, for the sake of the whole world that the Church must be not simply united but form a visible unity, based on ecclesial structures that portray and express what the Gospel is about, namely the Kingdom of God. This leads us back to the points we made earlier on: institutional matters are inseparable from theology; word, sacrament, and institution form one unbreakable unity so that if any one of these is found to be deficient, the rest of them are seriously affected. An ecumenism that does not take seriously this unity—and signs of such an ecumenism appear quite often in our days—will not lead us on the right path to unity.

The second point stressed by the Archbishop in his address, which I think deserves underlining, is the one illustrated by the story of reading the story-book from the last page backward. It took us a long time in theology to cease treating eschatology as the last chapter of dogmatics. Some of us still treat it in this way, but we are all gradually learning that the Omega is what gives meaning to the Alpha. And by having first a right vision of the future things, of what God has prepared for his creation in the end of time, we can see what is demanded of us in the present. Such an eschatological outlook liberates us from the evils of provincialism and confessionalism, which threaten our Churches constantly, and broadens our perspective so as not to exclude from our concern for unity people of other faiths and even those who doubt and seek after the unknown God. This makes the Christ whom we regard as the only Saviour the true ἀνακεφαλαίωσις (recapitulation) of all, and the Church truly Catholic as the eucharistic celebration wants it to be.

Ecumenism needs a vision. We cannot go on seeking unity by treating the Church as a fundamentally social institution. We have to ask ourselves constantly whether what unites or divides us matters eschatologically, whether it affects the destiny of God’s world as He has prepared it in Christ. I fear that we often give the impression that we have no vision in our ecumenical endeavours. That we either quarrel about issues of the past or about matters that can make headlines for the news of the day, without asking the question of ultimate significance in these matters. We thus risk seeking a unity different from the one our Lord had in mind when He prayed that we all may be one. For his prayer did have a vision and indeed a theology behind it. It was a vision of unity modeled on the doctrine of the Holy Trinity.

We have many reasons to be grateful to Archbishop Runcie for giving us so many and such deep insights into the question of the unity we seek. I hope that my modest response to his address has not obscured too much these clear and invaluable insights. This would make it perhaps worth the patience you have shown in listening to me. Thank you.

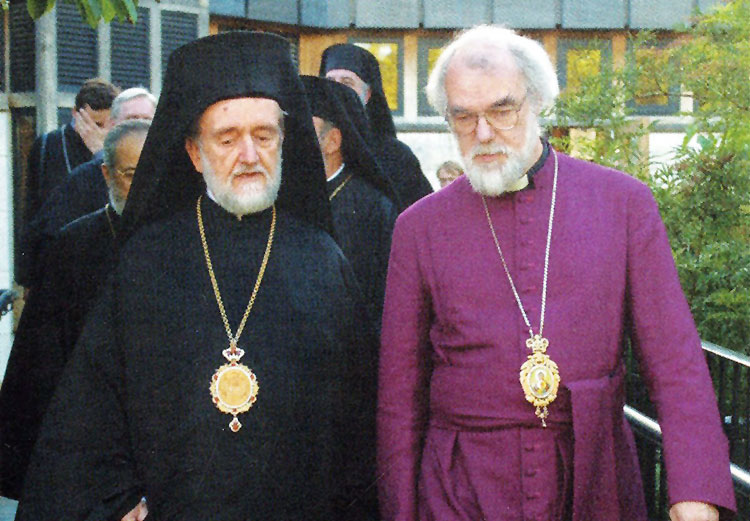

* This Synod meets every ten years in the center of Anglicanism, in Lambeth, London, and all Anglican bishops around the world participate in it. During the Synod in 1988, the Archbishop of Canterbury invited John Zizioulas as the main speaker in response to his own speech on the theological problems for Christian unity. That speech (see publications) was widely and positively commented on in the daily press of England.

Source:

The One and the Many. Studies on God, Man, the Church, and the World Today, ed. Gregory Edwards, (Los Angeles: Sebastian Press, 2010), pp. 365-372.